Week 16: What if the war doesn’t end?

In this issue: ▸ The endless war ▸ The war deepens poor countries’ debt woes ▸ Happy Earth Day, or? ▸ Fund managers stick with fossil fuels ▸ Atmospheric methane hits record high ▸ And much more...

Dear all,

Silence. Not a comfortable one. No, hysterical silence. Screaming silence.

Images from the war in Ukraine, dead people, bombed cities, atrocities, on the TV screen and in the newspapers, mixed with latest news about inflation and poorly performing stock markets, as well as the big read for the weekend about Netflix and future of streaming…

The endless war

The war in Ukraine needs to stop. Now. Sanctions, more weapons, more countries like Finland and Sweden running to NATO to feel safe. At any cost.

After eight weeks of war, far longer, seemingly, than either side anticipated, it is a real possibility that neither country will achieve what it wishes to achieve.

Ukraine may not be able to expel Russian forces fully from the territory they have taken since Moscow launched its invasion in February.

Russia is likely unable to achieve its main political objective: control over Ukraine.

Instead of reaching a definite resolution, the war may well usher in a new era of conflict characterized by a cycle of Russian wars in Ukraine.

If the war does not end anytime soon, the crucial question is: Whose side is time on?

A protracted war, lasting from months to years, might be an acceptable and perhaps even favourable outcome for Moscow. It would certainly be a terrible outcome for Ukraine, which would be devastated as a country, and for the West, which would face years of instability in Europe and the constant threat of a spill over.

A long-term war would also be felt globally, likely causing waves of famines and economic uncertainty.

A forever war in Ukraine also runs the risk of eroding support for Kyiv in Western societies, which are not well positioned to endure grinding military conflicts, even ones occurring elsewhere. Postmodern, commercially oriented Western societies accustomed to the amenities of a globalized peacetime world could lose interest in the war, Russia’s population, which Russian President Vladimir Putin’s propaganda machine has agitated and mobilized into a wartime society.

Although the United States and its allies are justified in hoping for and working toward a rapid Ukrainian victory, Western policymakers must also ready themselves for an extended war.

The policy tools at their disposal—such as military aid and sanctions—will not change relative to the war’s duration. Maximum military support for Ukraine is essential regardless of the war’s trajectory.

Sanctions targeting Russia, particularly aimed at the energy sector, would ideally lead to changes in the Russian calculus over time, and are well suited to engineering the long-term decline of the Russian war machine.

The key challenge resides not so much in the nature of support for Ukraine. It resides in the nature of support for the war within the countries that are backing Ukraine.

In an age of social media and of image-driven emotionality, public opinion can be fickle. For Ukraine to succeed, global public opinion will have to hold strong on its behalf. This will depend, more than anything, on adept and patient political leadership.

Read more.

The war deepens poor countries’ debt woes

Turning tables, shifting geopolitical priorities and consequences we cannot even comprehend right now.

The war in Ukraine is making it tougher for many emerging-market governments to make debt payments to foreign creditors, fuelling concerns of potential crises that could shake markets and weaken the global economic recovery.

Many of these countries accumulated mountains of debt during the past decade while inflation and interest rates were low and in the past two years when Covid-19-related costs were climbing. Now, from Islamabad to Cairo to Buenos Aires, government officials are struggling with rising import prices and debt bills on top of the continuing pandemic.

“There are going to be defaults. There are going to be crises. When we are hit by shocks like this, anything is possible,” Kenneth Rogoff, a Harvard University economist, said during a recent IMF panel discussion.

Combined global borrowing by governments, corporations and households jumped by 28 percentage points to 256% of gross domestic product in 2020. That is a level not seen since the two world wars during the first half of the 20th century.

About 60% of low-income countries – defined as the roughly 70 nations that qualified for a global debt-payment suspension program during the pandemic – were at high risk of debt distress or already in distress in 2020, up from 30% in 2015, according to the IMF.

China’s share of external debts owed by the 73 highly indebted poor nations jumped to 18% in 2020 from 2% in 2006.

Meanwhile, the combined share of traditional lenders – multilateral institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank and the “Paris Club” lenders of mostly wealthy Western governments – fell to 58% from 83%.

It is strategic debt we are talking about. It gives you a hunch who controls the reins and how the world will be shaped over the next 10 years.

Read more.

Happy Earth Day, or?

Earth Day. What does it mean? What are we celebrating?

The world has warmed about 1.1C since pre-industrial times. It is so exhausting to believe that the world is bad or lost.

There just really isn’t any option besides trying to push forward, persist in the hope that something will be done, even despite a great deal of evidence pointing to the contrary.

Or, as Oscar Wilde famously put it, “the triumph of hope over experience.”

The environmental problems that led to the creation of the first Earth Day in 1970 included (among many) air pollution that made people sick, pesticide pollution that made birds die and water pollution that made rivers burn.

Today, Earth is facing a ‘triple planetary crisis’: climate disruption, nature and biodiversity loss, and pollution and waste. This triple crisis is threatening the well-being and survival of millions of people around the world.

April 22nd can feel a bit exhausting if you are someone who cares about the environment or, to go a step beyond, someone who tries to maintain the integrity of the climate on this planet.

You recycle, even though you know recycling is very flawed. You try not to eat a lot of red meat, even though you know individual action won’t fix climate change on its own. You never miss a local election even though some politicians continue to discuss global warming as a hypothetical. And now the day has once again arrived for you to “celebrate” the planet while being acutely aware of just how much we’re trashing it the other 364 days of the year.

The idea with Earth Day was the brainchild of Senator Gaylord Nelson, who had been trying to make environmental issues a political priority in the U.S. for years without any real headway. And the first Earth Day was a resounding victory: With roughly 13,000 demonstrations and events across the US, it captured the attention of the country on the urgency of the national pollution crisis, which paved the way for the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency in US.

But after 51 years, Earth Day has buckled somewhat under the weight of the world’s environmental problems. Perhaps because those problems have become increasingly imminent, life-threatening (on a human species scale), and complicated to address both diplomatically and politically. And rather than stake hope in a widespread societal overhaul, many understandably overwhelmed people have adopted the “do what you can” approach when it comes to personal environmental footprints.

Indeed, Earth Day’s 20th anniversary in 1990 helped to usher in the idea of green consumerism, complete with big corporate sponsors. Big brands and corporations really took that marketing angle and ran with it right up to today, which is probably no small part of your disillusionment.

It can be hard to avoid thinking that a day that was meant to be both celebratory and revolutionary has become so appropriated that it’s a tawdry insult to real progress.

Nelson’s real intention was that Earth Day would be about, believe it or not, soul-searching. And change that addresses the root causes (like structural inequality, consumerism, racism) of something as seemingly straightforward as pollution requires a real assessment of what we want for the future and why, no?

Fund managers are sticking with fossil fuels

Last week, Reclaim Finance and three partner NGOs released a scorecard ranking 30 major asset managers on their climate commitments, with a focus on their approach to the fossil fuel sector. The analysis provides new data on their exposure to companies with the biggest fossil fuel expansion plans.

Of the 30 asset managers that were assessed, 25 are members of the Net Zero Asset Manager Initiative (NZAM). Yet not a single one of them has set the expectation that companies in their portfolios should quit developing new coal, oil or gas projects in line with climate science.

The 30 asset managers assessed hold more than $82 billion in companies developing new coal projects. The numbers are even more staggering for the oil & gas industry: together, the 30 asset managers hold $468bn in 12 major oil and gas companies with massive upstream expansion plans.

The report finds that their policies and investment guidelines, due to vague criteria that leave the door open for the worst polluters, are too flawed for the asset managers to align their entire portfolios with a net zero target.

Here are the highlights:

17 asset managers now have a coal policy and 12 have an oil and gas policy. Vanguard, State Street Global Advisors and Allianz’s asset management branch PIMCO are among the biggest firms with no fossil policy at all.

Among the asset managers with policies, only seven restrict investments in companies developing new coal projects, a number that hasn’t changed since last year, and none restrict investments in companies developing new oil and gas supply projects.

More and more policies introduce exceptions to exclusion criteria. For instance, among the seven asset managers that restrict investments in companies developing new coal projects, three plan to introduce undefined exceptions to this rule.

Even more worryingly, scrutiny reveals a growing trend of policies and targets that apply only to a small share of the asset managers’ assets.

None of the asset managers apply their existing fossil fuel restrictions to all their ‘passively’ managed assets, which is particularly concerning considering ‘passive’ investments keep growing and represent 46% of the assets covered by the report. The nine biggest ‘passive’ asset managers within our sample of 30, are also among the biggest holders of companies developing new coal projects. This is due to none of them applying robust coal criteria to their ‘passive’ funds.

Ten of the asset managers have released 2030 decarbonization targets, however, the targets only cover a small share of their portfolios.

The deeply disappointing findings revealed in the scorecard were published one day ahead of the one-year anniversary of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ).

You can find the scorecard and analysis here:

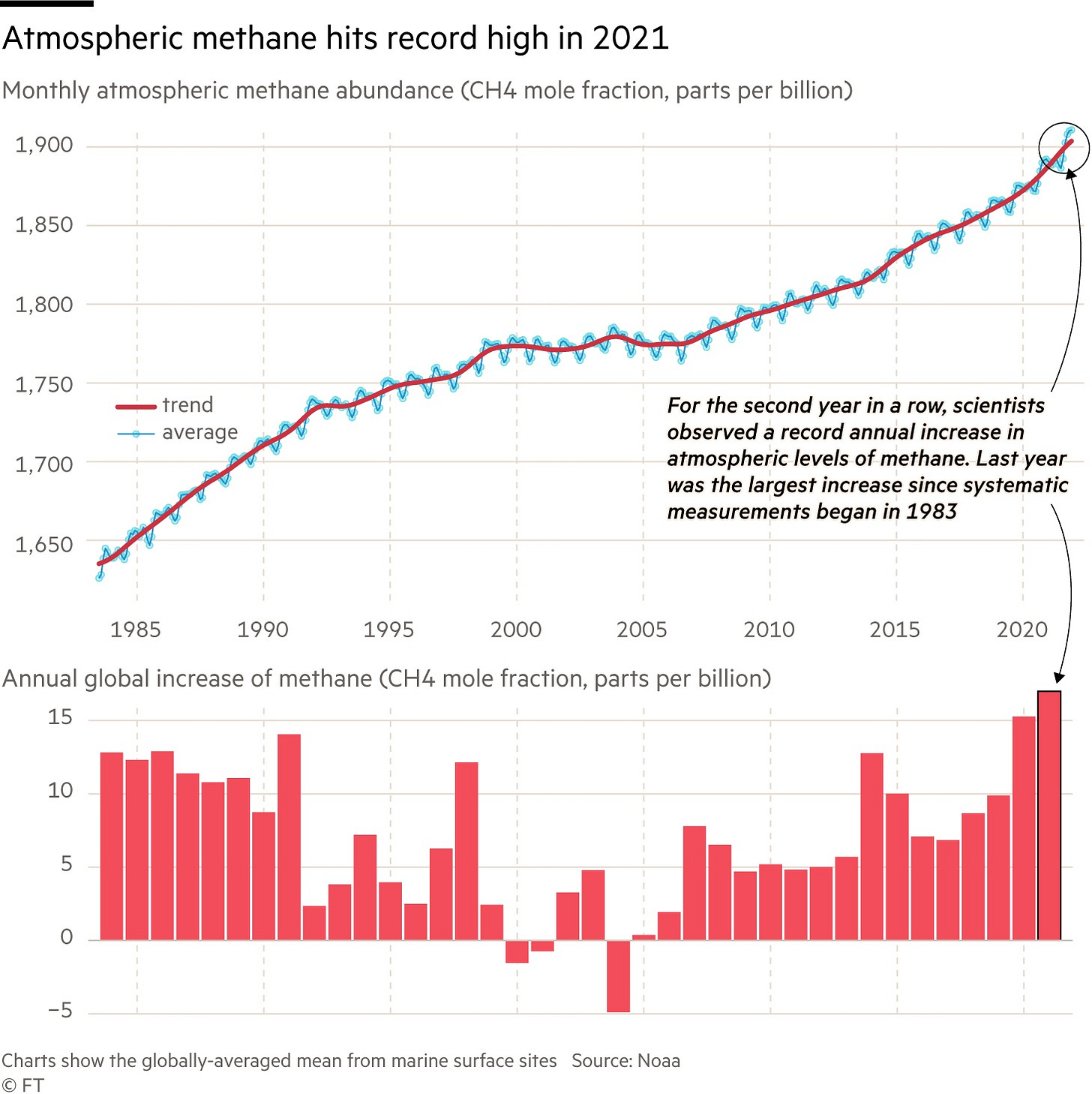

Atmospheric methane hits record high

We end this week with more bad news, I’m afraid. Atmospheric levels of methane, a warming gas that is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide, surged last year and hit a record high. Read more here and see the graphs below.

It looks bad, but let’s stay hopeful…

Kind regards,

Sasja